■Special Discussion■ “Herb Prince” Tomomichi Yamashita and CEO Ishizaka had a conversation about “wild plants.”

Knowing about wild plants can change your world

Yamashita Tomomichi, who wears many hats including wild plant researcher, mountain vegetable expert, wild plant florist, and nutritional education instructor, is known as the “Herb Prince.” Through workshops and wild plant guides, he strives to preserve and pass on the wisdom and traditions of Japan’s ancient herbs and wild plants.

He spoke with Ishizaka Noriko about the use of satoyama and environmental changes, using wild plants as a starting point.

Ishizaka: Your mother loved flowers, and your father was a mountain climber, so you had many opportunities to come into contact with plants and nature, but I don’t think it’s easy to acquire that level of knowledge. What was it that made you so fascinated with wild plants, rather than just liking them?

Yamashita (hereafter, titles omitted): I’ve been practicing flower arranging since I was four years old, and the flowers I used to arrange were so-called mountain wildflowers like witch hazel and wintersweet. At first, I was reluctant, but then I got more and more into it, going to the mountains to cut flowers and arrange them, and I grew to love it.

Plants always appear in the ancient Japanese Man’yoshu and Kojiki. Every plant has a history, an origin, and a name. Unraveling this connects various ancient cultures. Wild plants are always included in Japanese food culture, and once you understand the meaning behind them—for example, “This plant is found in this region, and this region makes kusa-dango (rice dumplings)”—it’s fascinating even just walking around. I’ve always loved antiques, so I find it very enjoyable when “history” and “plants” come together.

Ishizaka’s approach to wild plants is linked to “tradition” and “history,” which is consistent with our company’s approach to satoyama.

Yamashita : Another reason is that each one has a completely different face. Even if you try to remember just one type of dandelion, you’d need to know about 30 different types of dandelions to properly remember them. I have a collector’s urge, so by collecting specimens and keeping them at home, I naturally learned them.

What was the trigger that led you to start going beyond just looking at Ishizaka’s illustrated guide and actually going to the locations to look for them, sketch them, and make them your own?

When I was holding observation events at Yamashitayama , I was very happy when customers said to me, “You answer all my questions,” and it made me think, “If I could understand all of Japan’s plants, I could hold observation events anywhere in Japan.” Then, my desire grew stronger, and I thought, “I want to be able to observe them in the sea even when I go to the ocean,” so I learned about seaweed. My current goal is to thoroughly understand all 10,000 species of plants in Japan.

Ishizaka: Vegetables and wild plants may seem similar, but they are completely different. Why did you become interested in wild plants instead of vegetables?

Yamashita : Maybe it’s because you can pick them and eat them right away. When I first moved to Tokyo from Kyushu, I was surprised at how expensive vegetables were. When lettuce was out of stock, I would pick dandelions. I think the appeal is the ease with which you can pick them and cook them, as long as you have the knowledge.

But growing wild plants is quite difficult. Vegetables have a consistent germination rate, but the germination rate of wild plants varies throughout the year, so there’s no stable supply, and they can’t become “vegetables.”

Ishizaka: Nowadays, vegetables are becoming more and more valuable, but the new value of wild plants is still unknown. Wild plants are beautiful, aren’t they? I would like people to experience that beauty.

What do wild plants mean to you, Yamashita?

Yamashita : It’s something you devote your life to. You can spend your whole life with wild plants. The more you do it, the more you sink deeper into it, or rather, it’s too deep.

At Ishizaka Observation Groups, what do you tell people who say, “I’m vaguely interested in wild plants, but I don’t really understand them yet,” about the appeal of wild plants?

Taking Yamashita dandelions as an example, by weaving in stories about food culture and lifestyles not only in Japan but also in other regions, such as “This is how it’s used in Egypt and Europe,” or “In Italy, it’s more expensive than lettuce,” new discoveries can be made, such as finding out that it’s in borscht or that it’s used as an ingredient in this lotion.

Ishizaka: It’s certainly fascinating to see such a way of communicating! It’s not just about conveying the characteristics of each wild plant, but also about how they are treated and viewed around the world, which brings out the most interesting aspects of the plant.

Yamashita: That’s right. 80% of the people who participate in observation events and other such events are interested in “how they can be eaten.” Most of them are interested in how to eat them and their medicinal properties.

Ishizaka: Many people don’t know how attractive it is, so I think it’s important to know how to convey its appeal. When someone with a wealth of knowledge like Mr. Yamashita comes to the area, I think it makes people realize, “Oh, really?” and “I want to cherish it.”

Ishizaka: From an environmental perspective, has there been any impact or change on wild plants?

Yamashita : Yes, native species are decreasing. For example, there is a small blue flower called the persian jasmine. It is rapidly increasing in number, while the endangered persian jasmine is rapidly decreasing in number. New towns are being developed, and various seeds are being introduced with the construction, which is causing an increase in invasive species (naturalized plants) and a decrease in native species, and this impact is clearly evident.

Ishizaka: The general public doesn’t know that there are native and non-native species of wild plants. It’s the same with vegetables; most of the vegetables currently on the market are “F1 species (*1),” but at Ishizaka Farm we focus on cultivating “endemic species (*2).” We

were talking about dandelions earlier, but what is the “value of Japanese dandelions,” for example?

Yamashita: The common dandelion reproduces by self-pollination, but the Japanese dandelion cannot reproduce without cross-pollinating with other dandelions, so its numbers are currently declining rapidly.

It is delicate, but its seeds are large, and the Japanese dandelion is actually smarter. Its germination rate is overwhelmingly high, and it has a system that allows it to sleep in the summer and wake up in the winter. I think the Japanese dandelion has the most advanced way of life among all dandelions (laughs).

Ishizaka: I didn’t know that!

In terms of habitats, pouring concrete is eliminating the places where wild plants can grow.

Yamashita : Plants that can survive in such an environment have survived, but the delicate plants have disappeared. That’s why many of the plants that grew around rice fields are designated as endangered or near-threatened species. Another factor is the effects of pesticides causing seeds to explode. The number of species such as Tabirako (Lamium amplexicaule), one of the seven herbs of spring, has decreased significantly in the Kanto region. Because there are many areas where satoyama (satoyama forests) are left unattended, the number of dogtooth violets and other plants has also decreased.

Ishizaka: I think that by linking satoyama with wildflowers, we can reevaluate it from the perspective of satoyama. If

we could communicate what kind of added value is created when looking at satoyama from the perspective of wildflowers, I think we could see a path to resolving the problems facing satoyama all over the country. When we

think about increasing the added value of satoyama and making the most of it, we tend to look at it from the perspective of “satoyama from a human perspective.” Rather than considering whether it has value from a human perspective, if we think of it as “satoyama from an ecological perspective,” we see that the food chain continues unbroken there. I would also like to see it communicated as an “ecological treasure trove.”

The weeds that grow in satoyama and natural forests are different, aren’t they?

Yamashita : It’s different. If you don’t take care of it, golden orchids and silver orchids will never appear. The presence of such rare plants means that the area is being properly cared for. Even the giant-leaved dragonfly flower is delicate, so it’s easy to see that it’s being cared for.

Ishizaka: Even if we are managing and trying to protect something, as soon as we tell people that it can be used, there will be people who take it. So, just like “enjoying it quietly,” wild plant fans need to know the limits.

Of course , you are welcome to pick wild plants, but it can be a hassle if you pick rare species. We sometimes refrain from telling people who want to pick them.

I think that the plants of Ishizaka Satoyama, like alpine plants, are beautiful because they are here. If things that grow naturally are picked, they will disappear, so I want people to enjoy the fact that they are here. “Nature” may be inherently free, but our intention in preserving and managing the area is not for humans to control nature, but rather to view Satoyama as “a place where we can play in the ecosystem.” We carry out activities and provide explanations to help people understand this way of thinking. While we

want to increase the number of wild plant fans and get them interested, is there any message you would like to see in regards to certain things that should be protected?

Yamashita: There are plants that are fine to pick in large quantities, but there are also many plants that will disappear if you pick just a few. I think there are also cases where people pick them unintentionally, but because they lack knowledge. That’s why I want to spread the word that there are species that can be protected if they are picked correctly and with knowledge.

Ishizaka: Mr. Yamashita has an extraordinary spirit of inquiry. It’s amazing that he has researched and systematized his knowledge on his own, even though there were no textbooks to follow.

For example, it could create a new job, such as a “wild plant doctor,” who gives advice on wild plants.

Yamashita: That’s interesting. You’re not a tree doctor, but a wild plant doctor. Recently, there are a lot of people who want to incorporate wild plants into their gardening.

Ishizaka : You are a “wild plant researcher,” and what kind of work do you do?

Yamashita: Wild herbs have recently been getting a second look, and I’ve been appearing at a lot of events and on TV. But I don’t want this to end as just a passing fad. I want to make it “normal” to have wild herbs in our lives. I think it would be good to drink wild herb tea instead of coffee, or to incorporate them into bread, and I would like to see more use of Japanese herbs.

Do you want to incorporate Ishizaka wild plants into your daily life so that they can replace herbs?

Yamashita: That’s true. They grow in my own home, so they’re more familiar to me. I want to convey the value of Japanese herbs.

Is there anyone whose life has changed since learning about Ishizaka Wildflowers?

Yamashita: Many people say that their lives have become more thoughtful. For example, they try adding chickweed to their bath. I personally feel that they can spend each day more thoughtfully. Just thinking about using this in a dish makes me excited, and it also helps with daily healing. It’s great to be able to sense the seasons through plants.

Ishizaka: It’s really important to feel happy through wild plants. I think a lot of people will relate to messages like how wild plants can enrich your life, make you feel the four seasons, and help you live a more considerate life.

Yamashita: I started studying wild plants seriously three years ago, and the number of times I’m moved has definitely increased. It’s about ten times more. I’m now moved just by discovering something that I never noticed before, like “Oh, this is growing here.”

Ishizaka : I think a high level of sensitivity is also important. Some people enter the same forest and feel nothing. If you don’t have the ability to sense it, you won’t feel anything. I feel there is a lot to be gained by interacting with nature. It’s wonderful how wild plants can change your outlook on life.

How would you sum up the appeal of wild plants in one word?

Yamashita : It’s difficult, isn’t it? There are so many things to consider…

But one thing I can say is that wild plants have broadened my world and enriched my life in so many ways. I’ve met so many people thanks to wild plants and other animals, so I feel I need to give back to them.

Ishizaka: Are there many other people researching wild plants who, like you, are systematizing and communicating about wild plants as a whole?

Yamashita : There are very few. There are specialists in each field, but there are very few people who can explain everything, including plants, trees, and vegetables, so I would like to become that kind of person.

Like Mr. Ishizaka Yamashita, do you also have a desire to increase the number of people across the country who can speak it?

Yamashita : Of course. I have a desire to develop people.

I would like to make use of the Ishizaka Satoyama fields to create a place where people can learn about wild plants both in the classroom and in the field. I think this is a Japanese value that we can be proud of around the world.

Yamashita: There are so many great learning materials available. It’s completely different when you study in a classroom and then look outside. It’s not enough to do just one or the other; you also need to organize what you see outside inside, and both are important.

Ishizaka: Many people don’t know much about ecosystem chains, so I’d like to work together with them to explore possibilities and find ways to use the keyword “wild plants” to solve issues related to the environment and biodiversity.

*1 F1 species: A type of artificially improved variety that is known as a first generation crossbreed and is suitable for mass production and stable supply.

*2 Indigenous species: “ordinary vegetable seeds” that have adapted to the climate and soil over a long period of time.

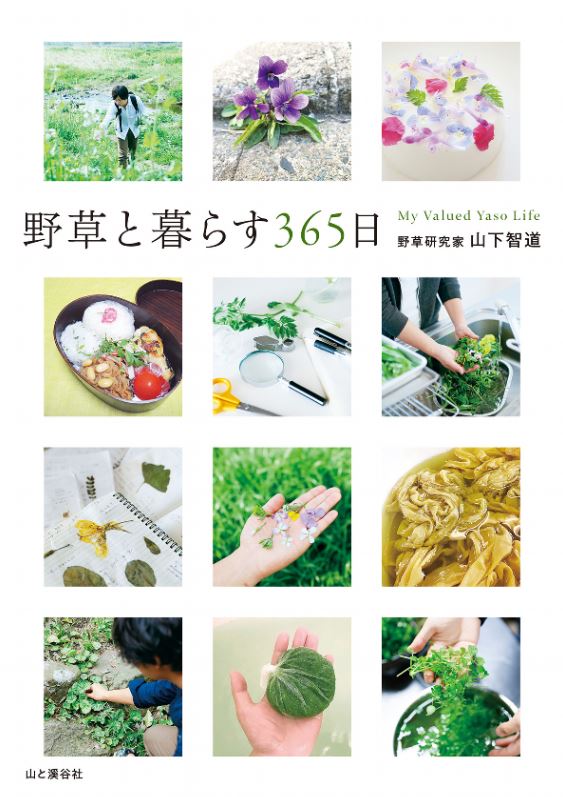

◇ Profile of Yamashita Tomomichi

Born in Kitakyushu, Fukuoka Prefecture in 1989. Influenced by his parents, he has been interested in plants and wild plants since childhood. After graduating from high school, he moved to Tokyo and worked in the entertainment industry. In 2015, he began full-scale research into Japanese wild plants as the Herb Prince. He has obtained the Medical Herb Certification and Wild Plant Knowledge Certification, and is actively engaged in educational activities about wild plants, such as hosting wild plant walking guides and workshops all over Japan, in order to convey the appeal of wild plants and herbs. In 2018, he published the book “365 Days of Living with Wild Plants” (Yama to Keikokusha).

Herb Prince Official Fan Site: https://www.tomomichi-yamashita.com/

Facility Tour and Training Program

We offer factory tours throughout the year that are open to all visitors.Our programs include tours designed for adults, family-friendly tours for parents and children, as well as tours tailored for companies and organizations.We provide customized courses based on your needs, including the theme, budget, and available time.

Contact Us

For inquiries regarding industrial waste acceptance, media interview requests, or consultations about collaboration and partnerships, please contact us here.